Content warning: discussion of rape in video games.

It’s like a wave is rolling in, borne of several currents: a Nightline special, an errant tweet, a sequel to a hot gaming franchise. People wondering if we’re going to “start” having this conversation of how to “tackle” rape in video games, but I don’t feel like the conversation ever has stopped. It never, ever stops for me.

Sometimes it feels like the discussions that rape and abuse victims have among themselves is significant and invisible. We pass along content and trigger warnings for shows or games we consume. We acknowledge something off to the side, just out of your line of vision, a thing that lurks in the dark. If you believe that the games industry cannot discuss or approach a conversation about rape, I believe it is because many people feel like we are set apart from this somehow. It doesn’t acknowledge that you might not know who is a victim or a survivor. You don’t know who could contribute or maybe the ways that we have been, all along.

Rape is a topic I’d be okay with striking altogether from gaming, outside of victim- or survivor-written narratives. It’s obvious that the game industry barely recognizes what counts as sexual assault, let alone acknowledging that people are victims of it. The insistence to include rape in games creates this uneasy message that someone like me doesn’t belong here. Given that sexual assault is an assertion of systemic power and violence, it is grimly ironic.

I want to ask all of these developers, writers, a simple, “Why?”

Why put this in your game? Why this and not something else? It leads me to think that many find it essential as texture, to make the world “come alive.” It creates a world that so many don’t have to live in day-by-day but can participate in, like tourism. When you make a game and use it to bolster the game’s “realism,” what you’re telling me is that you need our suffering as a fixture in your world, placed just-so, like a lamp. What is actually disruptive violence in the real world, exists as something inevitable and crucial for your fictional one.

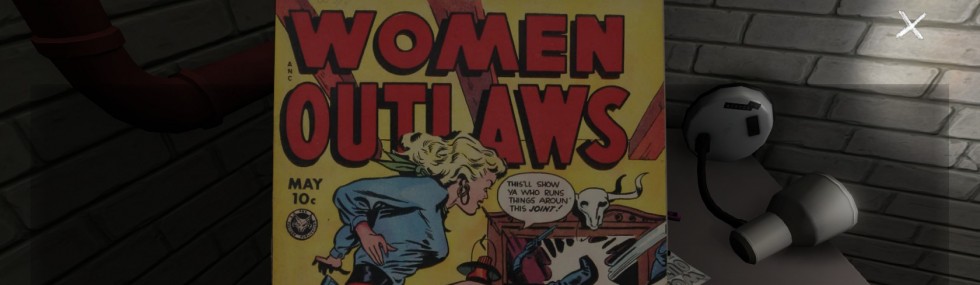

“But rape exists in movies and comic books too!”

When I watch a movie or read a comic book, there is a passivity there. I cannot affect the story at hand, I am not a part of it. I can either regard or turn away. The fact is that I have more control in being passive than what gaming frequently offers me. At best, a game’s interactivity absolutely positions us as a silent participant, a complicit bystander, with no ability to change course. At worst, it puts us into the position of the rapist. These are two alternatives that I cannot bear, time and time again. The fact that so many games rely on showing us these things and never center a victim or survivor in the narrative indicates that games care more about rape than those who are raped.

Rape is complex. It’s not picking the wrong item to equip or taking the wrong road. Games are focused often on player choice and it never seems to address that it is not about a victim’s choices, it is actually about a rapist’s choices. But the narrative never really reflects that, indicating that rape is just something that sort of happens. It also neglects that rape is the escalation of many more innocuous things in our culture. Rape culture, which feminists talk about often, isn’t just a buzzword - it literally describes the seemingly endless language that builds slowly to enable rape at all levels. Much like playing enough games gives you a familiar sense of inputs or consequences (jumping off a cliff often kills you, hitting D on a keyboard turns you right), rape culture is our society’s way of developing language to violate someone. We don’t value people’s personal spaces, we demand that women smile or allow us into their immediate vicinity. We overlook if someone is too drunk, we overlook if someone is uncomfortable with disagreeing, we value our own sexual desires over others needs or safety. We place certain groups above others, put people into power over others and give them the ability to enact it without culpability. We strip people’s ability to ever say “no.”

The pinnacle of this is often sexual assault, a finishing move.

“But this guy in the game is evil, that’s why he’s a rapist! It is showing us he’s bad!”

This is a lazy writing trope. It’s just as empty and useless as promoting this idea that all rapists are scary men that lurk in alleyways, that they are people you don’t know. Rapists are not always evil people that wear capes and kidnap young women. Rapists are often the hero, the friend, the family member. They are people who even might think of themselves as good, right, or justified. Many men can’t even reliably identify rape (or even would consider it) even when it is described to them, so how is an huge industry supposed to recognize it when they put it into games?

It is also laughably facile to position rapists as a villain, when it’s horribly rare that we even get to name our rapists in real life, much less bring them to justice. Many times in video games, the rapists are bad, but they are horizontal or parallel to the incredibly violent antagonist, because a victim would never be the person centered in the narrative, much less able to bring retribution on their attacker. If anything, the ability to enact revenge is only ever given to someone who is adjacent to a victim - such as a husband to a wife. Many times, victims are often people who are not even considered worthy enough to be a character. We’re dead and cast off to the side in places where it should be our story.

These are all things I’ve been trying to address in my work for a really long time, as someone who is a survivor and a feminist. The gaming industry has a long way to go because it barely understands how to see us as real people, but only cares as much as we can lend realism. The fact that most of us barely register as human beings means that it will not have the empathy or concern needed to put our stories first and foremost in a video game. The fact that games seem to value rapists over people who have been assaulted means I will always sit uneasily on the sidelines whenever this conversation comes back up, every single time.