This review/post contains mild story spoilers, so please play the game first.

This post also deals with personal, violent subject matter, so if that is triggering, feel free to skip sections 2-6.

1

I mean this as no disrespect, but I don’t expect men to write women, or girls, very well. There’s just something how most men push our narratives to the very edge of their awareness, stuff us into boxes. Men don’t listen. They don’t care. They don’t have our blood in their veins, our tender flesh held together with strings and whispers. Our stories squeeze in narrowly between theirs, and if no one believes us, we stop taking up space. We lose mass.

I still don’t know what kind of magic birthed The Uncle Who Worked For Nintendo into being. It has some of the same fairy dust as Gone Home, though the latter had more time to really dig itself under my skin. Gone Home had too many nuances to not be true. It was fiction, but it was clearly true.

The Uncle Who Worked For Nintendo, for people who have not played this short Twine game, is a fictional tale that on the surface works as typical creepypasta, but underneath is made up of real stuff. Hard stuff, scary stuff.

And underneath all of that is hopefulness, optimism.

I usually do not like games that give me too many endings. There’s always a nagging feeling that I’m not making the right choices, that I didn’t get the best ending.

—

I think something they don’t really tell you is that there’s some points in your life that will irrevocably change you for every moment that comes after. Time travel stories work on this principle but only to hand out platitudes about being unable to change the past. It has no real teeth, and it never tells you the real truth of forking paths: that you become this different person, the potentialities dropping off your body like gangrenous limbs.

I’ve struggled for so many years to not feel like half of a person, that some essential part of me fell away back in my teen years, that I didn’t make the right choice. I am not sure what I would do if I had the ability to turn back everything until then. Would I get the best ending then? What do endings mean when you constantly have to move forward no matter what?

no, turn back, don’t go in the room, run away, run far away, he’s a monster

I ended up running anyways, later into the darkness, scared

Monsters are real, they are real.

And part of me was left behind.

2

The Uncle, the literal uncle of the title, is a monster. We don’t know where he comes from or what he truly is but he represents that kind of terrible bargain we sometimes make, to just get by.

We become monsters to keep us safe, no one tells you that

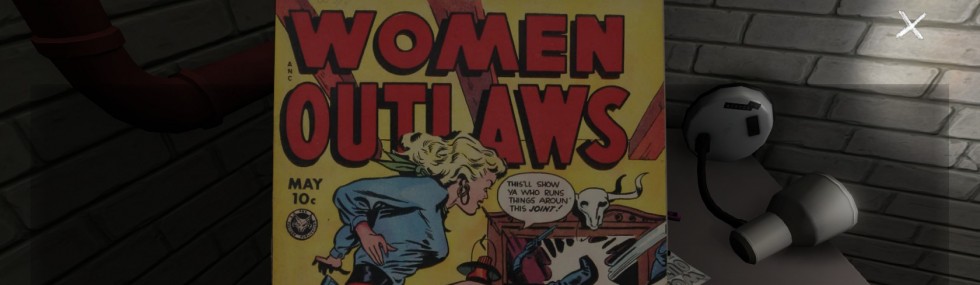

Your friend (I chose Jennifer) relates to you the misery that is being a girl who plays videogames. You know that feeling, that shared chasm that you fall into. Kids are cruel, you know, and it sets you up for the kinds of cruelness you deal with later on in life, that cruelness becomes part of you. But for that moment, you reach out to her and remind her that you’re there. That you are both real, and both wonderful.

Your friend has changed, you can tell. The events, the ones you remember, she doesn’t.

—

They don’t tell you that your memory goes, utterly. Bits of time are gone. There’s only holes, and blackness. Your ability to fragment a narrative is gone. Things shift around, uncomfortably, as some details burn white-hot in your brain while others fall away.

There were twinkly lights. It was red. The room was bathed in red light. Everything became red. There was a phone call.

I wouldn’t be able to sleep in a bed for years.

3

The uncle comes to the house and it becomes all too apparent what your role in this game is: sacrificial.

I ran to the door on my first go, trusting.

I knew better the second time and ran to the bathroom, hiding.

Fight or flight, no one tells you that the third option is to be so quiet and so still. Holding your breath. If I do nothing, the monster will leave.

But the Uncle is too smart, he knows where I am.

There’s more endings, I know there’s more, the lines are right there, and I can’t figure out how to get there, why the story keeps repeating and I cycle back to the moment when I can change things. I keep cycling back. It’s some detail, something I’m overlooking, I keep re-tracing my steps to see if I could have done something differently, it would all make sense.

You blame yourself a lot. A lot, over and over. They don’t tell you that monsters are monsters and that’s not your fault. It’s not your fault. You can do everything right, correct, perfectly, perfect perfect perfect and there’s nothing that can stop it. It’s out of your hands. It isn’t a wrong or right thing.

But I can’t even remember the story right.

4

It was the perfect Mew-two, that little key to your friend’s heart. The storm, the things that got changed when she made the deal with the Uncle. People started disappearing, but he made everything better, he salved the wounds.

Can you blame her? I can’t blame her. I would have made the same choice. We make these horrible concessions to ourselves, to other women, because it keeps everything copacetic. It keeps the anger at bay.

They don’t really tell you about the anger, the sticky disgusting rage that wells up in your eyes, your throat, that wishes to see him hurt, twisted, mangled like a corpse. Pushed into a compacter. Eaten alive. Stabbed with shards of glass. The anger is what is left behind when all the sadness burns away. People look at you differently, it is the darkness you run into, the monstrous hands you have. We don’t talk about it because it makes us less sympathetic, to coax a fire of hate around our hearts.

Your friend, she tells you, when you remind her that you are her friend, invited the monster because she was tired of being picked on. Even if it meant feeding everyone she cared about to him. It meant she got special gifts and attention.

It rang a little too true, for me.

I had a lot of girl friends in high school and we were inseparable. By college, I didn’t trust women, I said I never trusted them. It was a lie but I was so angry at myself, so I lashed out at other women for taking men away from me. Men, men, all the men, the ones who hurt me over and over again, but I kept hurting myself, hurting other women.

Throwing them away.

If I did that, then men would like me better. They wouldn’t hurt me anymore (yes they will) and we’d be fine.

So fine.

5

I’m stuck on this last ending. I look up a walk-through (a walk-through for a Twine game!) to help me. I see what I did wrong, I go back and fix it.

It’s okay to ask for help, they don’t tell you that. It’s always okay to ask for help, you’re not alone.

It’s safe in the kitchen.

I still eventually went back to get the failed ending. To see myself making that bargain, all over a Gameboy cartridge. It’s so easy to fall back into old habits.

Sometimes my friend dies in the fire, sometimes she moves away. In order to save myself, I have to let her suffer.

I need to do better this time.

6

We can save each other, together, hand in hand. We just have to believe each other, to show our secret hearts.

My secret heart is a scared 16 year old girl who made all the wrong choices, I can’t go back to that room and do it over again

You take your friend’s hand (that’s how I want to remember it) and you destroy the cartridge together. You’re both free. You don’t have to hurt eachother anymore, you don’t have to hurt yourself anymore. You don’t have to blame yourself.

We can be each other’s best endings, if we give ourselves space to fight the monsters together.

Secret Ending

The Uncle Who Works For Nintendo is a game I am still amazed was made by a man. There’s a simple lesson twisted around the agape horror, and that is if you care about yourself and care about your friends, you don’t have to despair. This is especially meaningful if you pick the slightly different story with a female friend, and that is the only one I ended up playing (I believe that the ‘other side’ is non-canon, for me personally. It is not a story I need to see, I have seen it a million times.)

The idea of two little girls holding hands and destroying a monster together is so powerful, particularly in the wake of the events that made the creator, Michael Lutz, skew the story and write the passionate author’s notes that accompany the game. It thoroughly touched me somewhere very deep and personal, in light of many other things that have been dredged up over the last year or so with my interaction with gaming and it surprises me because it’s not a story that gets touched on by men, who often don’t understand the true power of healing that comes from women bonding together. It’s just not something that has weight often in the stories of men.

But I love it, and I hope you love it and I hope you play it, if you haven’t already.